About

The Sutton Park Preservation Society (1894) & the Friends of Sutton Park Association (1950-Present)

It was the announcement of a plan to build a railway line through Sutton Park at the end of 1871 that led to the first public debate about protecting the beauty and tranquillity of that place. The vigorous campaign to prevent the opening of a railway line – led by the clergymen W.K. Riland Bedford and E. H. Kittoe, the physician James Johnstone and the edge tool manufacturer A.W. Wills – ended before a select committee of the House of Lords. The protesters did not meet with success and the railway line opened in summer 1879, but outrage over this ‘unspeakable’ and ‘atrocious’ development lingered for decades afterwards. The campaign marked the beginning of efforts by local people to obstruct developments which would fundamentally alter the nature of Sutton Park.

The Sutton Park Preservation Society was the first formal body established to defend the park. It came into existence in April 1894, prompted by the felling of trees to erect ‘disfiguring’ fences and what was seen as the ‘mind your own business, we shall do what we please’ attitude of the borough council. Eighty men rallied to the cause, a figure which soon doubled. Many of the most prominent inhabitants of Sutton Coldfield were involved, the chairman being Henry Duncalfe who had been the last warden before the establishment of an elected borough council in 1886. The aim of the Society was ambitious: nothing less than the removal from office of councillors who thought the park should ‘be treated as a commercial undertaking and … are unfit to safeguard its beauty.’ In a by-election in May 1894 the Preservation Society’s candidate E.J. Brookes was returned to the borough council, but Duncalfe ignored a challenge to come forward himself as a candidate in the municipal elections in November 1894. The Sutton Park Preservation Society proved to be short lived; Duncalfe died in October 1901.

There was no organised body to speak out against the proposals for tennis courts or a bowling green or outdoor games on Sundays in the first half of the twentieth century, but the newspaper correspondents remained busy. ‘When will our needlessly busy authorities learn that their duty in regard to Sutton Park is chiefly the very simple one of keeping their hands off it?’, one correspondent complained in December 1924. Referring to amusement parks in New York, another correspondent declared in August 1933 that Sutton Park is ‘becoming more and more like Coney Island every year. Those who control it should open their eyes to the danger and ensure that what remains of its primitive charm shall be maintained.’

The decision to reconstruct and refurbish huts erected in the park during the war as two- bedroom homes for twelve families in 1950 led directly to the establishment of a new organization to protect Sutton Park. This was the Friends of Sutton Park Association, which held its inaugural meeting at the church hall of St. Peter’s in Maney that December. Kenneth Blacklock, a businessman, was the key figure in this new move, becoming the first chairman of FoSPA. The aim of the new body was ‘to maintain the park against the covetous eyes of the War Office and the local council.’ In his attempt to prevent ‘the council creating a slum in the park’, Blacklock took up the issue of repurposing the huts directly with government ministers. He wrote to Hugh Dalton, the minister of local government and planning, and Aneurin Bevan, the minister of health, and subsequently was put through directly on the telephone to Bevan who, in a three-minute conversation, was ‘very pleasant.’ In his two years as chairman of FoSPA Blacklock was to expend many words – ‘very often hot ones’ – with government departments. The reconstruction of the huts had already begun, but Blacklock and FoSPA continued to protest at the involvement of the War Office in Sutton Park and at large areas of land being lost on ‘the altar of national expenditure.’ Blacklock announced that he would contest the local elections as a ‘Progressive Conservative’ in May 1952, but in the event this did not happen. By autumn 1952, when Blacklock stepped down as chairman to concentrate on his business interests, FoSPA had recruited 3,000 members.

In 1953 a new issue raised concern amongst lovers of the park. To enable the municipal golf course to be extended, the borough council decided to drain – at a cost of £2,685 – nearly nine acres of land near to Powell’s Pool. FoSPA naturally did not like the plan and the chairman Frederick Monks made clear that it would ‘try and educate members of the council to our point of view.’ Monks – who lost an arm during the First World War and subsequently became a senior figure at Dunlop – did not succeed in this ambition: there were members of the borough council who rather liked a round of golf.

The proposal in 1954 to stage the ninth world scout jamboree in Sutton Park led to fears amongst the membership of FoSPA that the arrival of tens of thousands of scouts would lead to a great deal of damage. Monks dismissed the claim by the mayor that the park would return to its existing state as ‘nonsense’, but, with assurances in November 1955 that no alterations made to the park during the jamboree would be permanent, FoSPA gave a guarded welcome to the event. The borough council did indeed seek to remove all traces of the event after it was over: there was extensive re-seeding and roads built for the occasion were removed. By the end of 1957 it was reported that ‘the park is rapidly returning to its pre-jamboree state’. D.J. Wightman, the chairman of FoSPA, declared that ‘the scouts have kept their promise.’

During the second half of the 1950s FoSPA continued to offer advice to the borough council. It campaigned – unsuccessfully – for Park House, recently acquired by the council, to become a local history museum and – this time successfully – against using the extensive grounds around the building for polo. It also made clear its opposition the lifting of a ban on golf and other organized games being played on Sundays, that day being when the park should be ‘enjoyed quietly.’ Litter had been a problem in the park since large numbers of visitors began to arrive at the beginning of the century. The solution, FoSPA believed, lay in caterers being compelled to provide more bins and the number of prosecutions for dropping litter – which carried a fine of £5 – being increased. In 1958 stepping stones were placed across footpaths in marshy parts of the park, largely at the urgings of FoSPA.

In its first decade of existence FoSPA certainly made its voice heard. To this day the Friends of Sutton Park continues to keep watch over the town’s greatest treasure.

Written by Stephen Roberts, January 2022

SUTTON PARK NATIONAL NATURE RESERVE

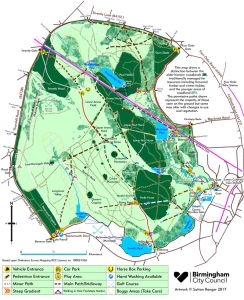

A place of unsurpassed biodiversity with heathland, wetlands and woodland. As such it means many things to many different people. Mostly Scheduled Ancient Monument but also Site of Special Scientific Interest, with most of the Park also included in the Register of Parks and Gardens of Historic Importance, acknowledging it’s precious archaeological remains. A legacy which must be protected now and for many generations to come. It’s stewardship and management must not be tarnished nor hindered by political bickering.

Obviously revenue is needed to fund the high maintenance of our ‘special place’ and the commercial attractions of the Mini Golf at Town Gate, boating on Blackroot Pool and the proposed Land Train from Banners Gate to Town Gate are appropriate to their location. However other proposals should be carefully thought through before inflicting irrecoverable damage. Car parking is a complex and contentious issue. Yes of course residents feel that their contribution of taxes to Birmingham and Sutton Town Councils is enough to grant them free access and who can blame them? Let us hope that the consultancy with residents will be properly conducted on an honest basis to discover the real thoughts of both Suttonians and all other Visitors.