Archaeology Stories

1300 BC

![bronzeagegroup[1]](https://www.fospa.org.uk/user/pages/04.archaeology/03.archaeology-stories/bronzeagegroup1.gif?decoding=auto&fetchpriority=auto) The sun is dipping below the horizon as the herdsman trudges homeward from the rough pasture with his sheep, which as usual show little inclination to keep together. Patiently he rounds up yet another stray. It will be good to reach home and get the sheep into the stockade for the night, safe from the

The sun is dipping below the horizon as the herdsman trudges homeward from the rough pasture with his sheep, which as usual show little inclination to keep together. Patiently he rounds up yet another stray. It will be good to reach home and get the sheep into the stockade for the night, safe from the ![sweatlodge[1]](https://www.fospa.org.uk/user/pages/04.archaeology/03.archaeology-stories/sweatlodge1.gif?decoding=auto&fetchpriority=auto) wolves which are a constant threat. His way takes him past the clan's sweat lodge and he smiles, recalling the pleasure of relaxing a few nights ago inside the shelter of bent and woven branches with the other men of the settlement. They had fetched water from the stream and poured it onto stones which had been raised to a fierce heat on a wood fire. Steam had filled the lodge and seemed to ease their aching limbs. The herdsman hopes that he can enjoy the experience again soon...

wolves which are a constant threat. His way takes him past the clan's sweat lodge and he smiles, recalling the pleasure of relaxing a few nights ago inside the shelter of bent and woven branches with the other men of the settlement. They had fetched water from the stream and poured it onto stones which had been raised to a fierce heat on a wood fire. Steam had filled the lodge and seemed to ease their aching limbs. The herdsman hopes that he can enjoy the experience again soon...

Today we can still see the 'burnt mounds' formed by piles of heat shattered stones discarded from these Bronze Age saunas, similar to used by some North American Indians. In the past it was thought they might have been cooking sites but no remains of food or cooking vessels have been found with them. The mounds are sometimes as much as 15m long but they are not obvious when they have become overgrown. Burnt mounds in eroded streams are a little easier to spot.

47 AD

![romans[1]](https://www.fospa.org.uk/user/pages/04.archaeology/03.archaeology-stories/romans1.gif?decoding=auto&fetchpriority=auto) An Auxiliary of the Roman Army - a long way from his native land - puts down his shovel and straightens his aching back. Since dawn his detachment has been digging two perfectly straight ditches ten metres apart. These have been marked out by the surveying officer to show the route to be followed by the legionary road to run from the fort at Metchley to Letocetum (Wall).

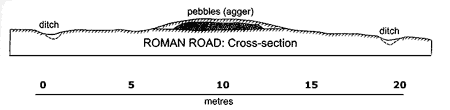

An Auxiliary of the Roman Army - a long way from his native land - puts down his shovel and straightens his aching back. Since dawn his detachment has been digging two perfectly straight ditches ten metres apart. These have been marked out by the surveying officer to show the route to be followed by the legionary road to run from the fort at Metchley to Letocetum (Wall).

All around him stretches barren heathland, where soon the military engineers will impose the alien line of a metalled road. The soldier has already marked several good deposits of gravel along the line of his ditch, so the engineers will have no problem finding plenty of material to make the road, a good thickness of compacted gravel, eight metres wide with a slight camber to throw off the rainwater. That should last at least twenty years, and keep Britannia pacified, he thinks...

Nearly 2000 years later, at the same spot, we can see the dead straight line of the road, which we now call Icknield Street, with its carriageway or agger, the guide ditches dug to the surveyor's instructions, and the pits which supplied the gravel to make the agger.

1170 AD

![deer[1]](https://www.fospa.org.uk/user/pages/04.archaeology/03.archaeology-stories/deer1.gif?decoding=auto&fetchpriority=auto) Thomas the Parker signals cautiously to his assistants. As they move forward, the herd of fallow deer stirs restlessly. At another signal from Thomas the beaters drive the herd towards the edge of the deer park. Soon the beasts are trapped between the men and the boundary ditch. There is no escape because the bank is topped by a paling, too high for the deer to leap over. The deer are driven along the edge of the park until they reach the gate to the deerfold (Driffold). Here, Thomas selects two dozen animals. These are to be sent as a gift from his master, William of Newburgh, Earl of Warwick, to the Bishop of Worcester to stock his new park at Alvechurch. Thomas has noticed a section of broken paling, and he orders one of the servants to mend it. This reminds him of the takes told by his grandfather of the great work of making the park. All the men of the Earl of Warwickâ?Ts estates were called upon to dig a ditch four feet deep and cast up the seven-mile-long bank round the park. Now it is Thomas's responsibility to ensure that the boundary holds good well into his own grandson's time..

Thomas the Parker signals cautiously to his assistants. As they move forward, the herd of fallow deer stirs restlessly. At another signal from Thomas the beaters drive the herd towards the edge of the deer park. Soon the beasts are trapped between the men and the boundary ditch. There is no escape because the bank is topped by a paling, too high for the deer to leap over. The deer are driven along the edge of the park until they reach the gate to the deerfold (Driffold). Here, Thomas selects two dozen animals. These are to be sent as a gift from his master, William of Newburgh, Earl of Warwick, to the Bishop of Worcester to stock his new park at Alvechurch. Thomas has noticed a section of broken paling, and he orders one of the servants to mend it. This reminds him of the takes told by his grandfather of the great work of making the park. All the men of the Earl of Warwickâ?Ts estates were called upon to dig a ditch four feet deep and cast up the seven-mile-long bank round the park. Now it is Thomas's responsibility to ensure that the boundary holds good well into his own grandson's time..

More that eight centuries later, extensive lengths of the deer park banks and ditches remain.A deer park was a medieval status symbol, coveted by every manorial lord. By 1300 there were deer parks at Shenstone, Hints, Drayton, Middleton and Great Barr as well as at Sutton, all within Sutton Chase. The Earl of Warwick has owned the hunting rights over this wide area since 1126, and Sutton Park was originally made so that the deer could be better conserved and managed than if they ran wild over the whole chase.

![mill[1]](https://www.fospa.org.uk/user/pages/04.archaeology/03.archaeology-stories/mill1.gif?decoding=auto&fetchpriority=auto) 1760 AD

1760 AD

Richard Reynolds the miller stands disconsolately outside his fine new corn mill at Longmoor Pool. Everything should be going well for him, but nothing has come up to expectations. Where is the volume of trade he had confidently expected? In reality the mill is too far away from the cornfields and the pool is too small to provide a good enough sustained flow of water. Enviously he gazes in the direction of Mr. Dolphin's new mill at Blackroot Pool. What chance does Reynolds have against those wealthy gentry, Mr. Dolphin and his partner Mr. Homer? They have been able to make a much bigger pool and their mill processes leather, not corn. Reynolds makes a decision. He will ask the Warden and Society (Sutton's Corporation) for permission to convert his premises to a ![mill2[1]](https://www.fospa.org.uk/user/pages/04.archaeology/03.archaeology-stories/mill21.gif?decoding=auto&fetchpriority=auto) button-polishing mill. With luck his business will then flourish for many years to come...

button-polishing mill. With luck his business will then flourish for many years to come...

Reynold's mill was demolished in 1938. It was only one of a dozen watermills carrying out industrial processes at various times in Sutton Coldfield. Today the tranquil pools at Longmoor and Blackroot show no trace of their industrial origins.